The New York Times | By: By Mitty Mirrer

This is what Memorial Day means to military children who have lost a parent.

Bayleigh Dostie was in kindergarten the year her family received a knock on the door. At 5:30 a.m. on Dec. 30, 2005, a scrolling news ticker reported that a soldier had been killed in Baghdad. Bayleigh’s mother, Stephanie, hadn’t heard from her husband in days and had a foreboding feeling that he was the dead soldier. She refused to leave her bedroom all day; she was afraid that military casualty officers would come to the house. And they did — at 2:30 that afternoon. Stephanie screamed for Bayleigh and her brother, Cameron, not to open the door.

Sgt. First Class Shawn Dostie was killed earlier that day by a roadside bomb in Iraq.

‘I wonder what kind of things that we would be doing and what kind of adventures we would be having if you were here’

In January 2011, Army First Lt. Demetrius M. Frison left for his first combat tour in Afghanistan. On May 10, 2011, he was killed by a roadside bomb. His son, Chris, is now 7 and lives in Manheim, Penn., with his mother, Mikki.

Bayleigh, and thousands of children like her, are America’s living lineage of parents who died while serving in the United States military. Whether the death occurred in a war zone or during peacetime, they experience not only the trauma of loss of life but also the additional loss of the family’s way of life. If the family lives on a military base, they must leave their homes and neighbors. Some children must also leave their schools and surrounding military communities.

My own father, a Marine, was killed in Vietnam, hours after I was born. As I grew up, Vietnam felt like a big secret. There were no support groups in place for military families, and many of us felt alone in our grief. Our loss was met with silence.

‘I’m not a little girl anymore, I just turned 20 and it is not easy becoming an adult without you’

Air Force Staff Sgt. Raymond Briggs died Dec. 1, 2010, in a car accident. His daughter Chelsea, 20, of Kapolei, Hawaii, wrote recently to her father to tell him she is now studying finance.

Today there are many more benefits for families who have lost a loved one, offered by the government and nonprofit organizations, such as the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors and the Children of Fallen Patriots Foundation. Every year, hundreds of families travel to Washington for TAPS’ National Military Survivor Seminar, where they learn coping strategies, share stories or just listen. These families are also reminded that they are not alone. By giving children the understanding and the tools to work with their grief — such as writing letters or in a journal — these programs help children grow through their grief.

‘I’m so glad you never had to retire your wings, even in Heaven’

Haley Hartwick, 22, of Reston, Va., wrote to her father, Army Chief Warrant Officer 3 Michael Lee Hartwick Jr., who was killed on April 1, 2006, when his helicopter crashed in Iraq. In 2017, she graduated from Baylor University with a degree in social work.

Bayleigh, now 18, was a sophomore at Fort Campbell High School when she realized she wasn’t able to hold in her sadness any longer. She cried randomly during classes. She struggled to concentrate on her work. She felt overwhelmed without any trigger. Each day, her painful emotions seemed to grow stronger. “I kept thinking about how he died,” Bayleigh said. “I had thought that I could deal with it myself, if I pushed it down then it would be O.K., I wouldn’t think about it as much, it wouldn’t make me sad all of the time.”

Bayleigh started going to counseling. She still ached to feel her father’s presence, but putting her feelings on paper helped her understand those emotions. “Working on grief booklets, writing letters and sending them off tied to helium balloons means more than anyone will ever know.”

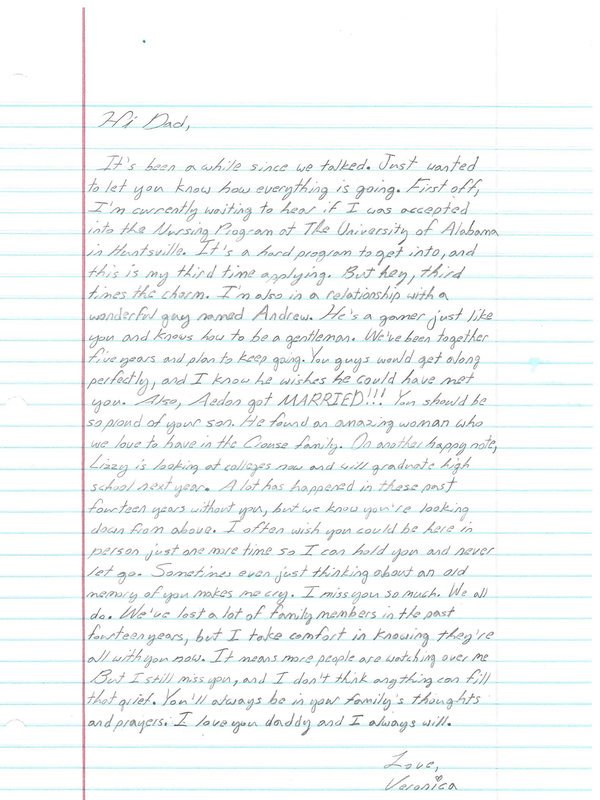

‘A lot has happened in these past 14 years without you, but we know you’re looking down from above’

Veronica Crouse, 20, of Huntsville, Ala., wrote to her father, Army Sgt. Robert Crouse, who died of an illness on July 8, 2004.

The day of her high school graduation, Bayleigh opened the curio cabinet that held her father’s pins and medals in the entryway of her family home in Clarksville, Tennessee. She thought a lot about her father in the months leading up to that day; he would miss another milestone in her life. “I don’t know how to deal with this,” Bayleigh said. “It’s one thing to hear advice from my mom, but it’s another thing to hear my dad tell me what he thinks and how he got to the point of when he graduated. It’s really just forcing me to process that he’s not here.”

Bayleigh Dostie, right, posing with her mom, Stephanie, at Bayleigh’s high school graduation. Credit Courtesy photo

Still, graduation made Bayleigh feel one step closer to being an adult. “I thought about what kind of person my father was and the kind of person he would have wanted me to be,” she said. “He had so much love to give, unconditional love. I want to carry that with me by being a good person, being humble and down to earth, and doing what is right — not just following what everyone else is doing.” When Bayleigh heard her name called and walked across the auditorium stage, she had her father’s jump wings — the ones she had found in the curio cabinet — pinned to her blue commencement gown.

Mitty Mirrer is a Gold Star daughter. She is a graduate of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and the producer and director of a documentary, “Gold Star Children.” You can read about her work at www.goldstarchildren.org.

The Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors and the Children of Fallen Patriots Foundation provided assistance in collecting the letters.